Why “Manly Virtue” Is Womanly

Chapter 4 of “You Shall Be Holy: Reflections on Orthodox Womanhood”

All through the ages and places where Christ’s Church has been founded, women have lived their faith boldly and quietly, as royalty and as poor widows, as wives and as virgins, as missionaries and teachers, as midwives and mothers, as monastics and as hermitesses, as martyrs and venerable eldresses in their communities. We have these witnesses to Christ as our inheritance, to show us the path of holiness is possible wherever and whenever we live.

–Anna Neill, “Starting the Brown Dress Project”

In this, the final section of Part I: Receiving God’s Love, we turn our attention from the way God loves us through the Holy Mysteries of Confession and Communion to the way He loves us in the communion of the saints. We discuss why the saints are important and how to cultivate communion with them, before moving on to what makes a saint, and what specifically makes a female saint.

Why Get To Know The Saints?

A friend was visiting a monastery at Mt. Athos while he was working on his PhD in Theology in Thessaloniki. An old monk was sitting in the courtyard, with a small group of pilgrims, between services…. [My friend] ventured this question,

“Geronta, how should I study the Scriptures?”

The elder looked at the young man intently for a moment and replied,

“You begin by reading the lives of the saints. They will show you the Gospels lived out in the world.” (“Starting the Brown Dress Project”)

Knowing the saints is a basic, crucial way to receive God’s love, by learning what He has been doing for our salvation ever since the beginning of the human race. Knowing the saints can be the difference between living our faith in black and white (just me and God) and in color (together with the whole family of God). The saints show us what is possible when we let God in and allow Him to transform our hearts.

The saints have this difference from ordinary people, that we can talk to them at any time and place, no matter where we find ourselves. So we are truly never alone. Just as we can always turn to our Heavenly Father or to Christ, we can always turn to these older brothers and sisters:

We Orthodox Christians live in a one story universe…. Those who repose have not merely become worm food and vanish into a great unknown…. When [we] say we live in a great cloud of witnesses (Hebrews 11 and 12:1), they continue to see the world because there is no death in Christ. Those the Church recognizes as saints have their holiness rise to the surface of our memories and their continued action within the Church serves as a confirmation….

You are never alone as an Orthodox Christian…. There is no suffering, no shame, no triumph, no need, no insurmountable task, no sadness, no joy, nothing that has not been shared by a fellow saint in their earthly struggle…. They can tell you every pothole, every twist and turn, dark corners where enemies lurk to pull you away from the goal. They can protect you, as a mother protects a toddler from rushing towards danger. Even if you are holed up for years in solitary confinement or hide on a rock in a desert, there you will find a feast prepared for you, with guests innumerable. (“The Saints Are Alive”)

“Cultivate communion with the saints” is Maxim #17 on Fr. Thomas Hopko’s 55 Maxims of the Christian Life, high on the list. In our culture, we aren’t apt to think of cultivating relationships with the saints as something urgent or even important. But when we take time to do so, then we can’t imagine life without them.

What Does Communion With The Saints Look Like?

We are not limited to conversation/prayer as a means of connecting with the saints. We also have relics and other holy things that show us God’s presence sanctifying the world through His holy ones, such as holy oil from the vigil lamp at a saint’s relics, myrrh that miraculously streams from icons or relics, and incorrupt relics. These are all powerful examples of how in Christ, nature itself is sanctified through the priestly ministry of the saints.

The saints are those Christians who really “got it” and so that is why we hold them up as examples. Because they were and are human beings like us, the fact that they are glorified in heaven has amazing implications for their fleshly relics, as well as the way we depict them iconographically. Perhaps even more wonderfully, many of these relics and icons produce additional miracles, such as the slippers of St. Spyridon which wear out on a regular basis, or the myrrh that flows from many icons and even from the relics of some saints.

Icons are often the way we get to know new saints, since ordinarily, we do not see them directly with our eyes (unless we visit their relics, or happen to know someone in real life who will later be recognized as a saint). Icons, however, are omnipresent: in church, in our homes, even outdoors!

In an icon, the peaceful, loving gaze of a saint fixes upon us, looking past our swirling thoughts, going straight to our heart. An icon communicates the saint’s essence to us, so icons themselves are holy. Many Orthodox Christians (perhaps including you!) have had a saving encounter with a saint through an icon. Gazing into a human face is so immediate, and when the person gazing back is further ahead than you on the spiritual path, they can beckon to you and encourage you to get back and stay on that path.

The saint I am closest to is probably St. Nicholas, the patron saint of the church where I grew up and one of the most popular saints in the world. Any Orthodox church you enter around the world is pretty much guaranteed to have his icon inside, and millions of Christians–Orthodox, Catholics and Protestants alike–joyfully celebrate his memory on December 6, especially when there are children in the house! As a teen, I was able to study abroad in southern Italy, close to Bari where his relics lie. Now, I find him a compassionate helper through parenthood.

Right now I have been calling on St. Nicholas to help me with, of all things, the stress of potty-training a toddler while in my third trimester. Keeping his icon before my eyes and anointing myself with myrrh from his relics, I am infused with just a little bit more supernatural patience, love, and insight that I need to navigate everyday challenges as a toddler mom.

In such everyday and miraculous ways, the saints represent and embody God’s compassion towards us, and encourage us to have compassion for one another and for ourselves. Sometimes when I feel like I’m drowning, instead of thinking the solution is to muscle up and keep going, it’s better to ask a saint for help first. I am always amazed at their generous compassion. Just as a phone call with a friend can offer comforting perspective in our moments of negativity and shame, the saints can also refresh us with extra hope, humility, patience, love, or whatever else it is we need in the current moment.

What Makes A Saint? (Holy) Eucatastrophe

What makes an ordinary person into a saint? One aspect of saintly identity is how these people responded to challenging circumstances or tragedies in their life. To describe this dynamic, Anna Neill borrows the term “eucatastrophe” from Tolkien, adding the adjective “holy”:

A recurring theme in good hagiography is one of holy eucatastrophe. This term, coined by J.R.R. Tolkien, is commonly defined as the happy resolution, an impossible problem which is solved by the end of a story. Why do I predicate eucatastrophe with the word holy? In the lives of saints, the plot twist in their lives is not usually rectified to the same status they were before. They may not have another child or remarry or regain wealth or live in peaceful times, all tropes we like to read or see in fairy tales. The resolution, the good to come from disaster, is a transformation of this person’s life path for their salvation, the choice to do good. (“Saint Sophia of Thrace and What to Do Next”)

Tragedy comes to us all. The question is how we respond, for every instance of suffering is an opportunity to become a little bit holier, more loving, more patient, wiser. As John F. Kennedy said, “In the Chinese language, the word ‘crisis’ is composed of two characters, one representing danger and the other, opportunity.” For example, many saints saw the threat of martyrdom as an opportunity to find eternal rest and life in Christ, outweighing the physical danger of losing their mortal life.

One incredible example of holy eucatastrophe, someone who responded to tragedy by transforming her heart, life, and entire community, is the Grand Duchess Elizabeth, also known as St. Elizabeth the New Martyr. Born Princess Elisabeth of Hesse and by Rhine in 1864, she married the Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich in 1884. They lived together happily, first in a palace in St. Petersburg, and later in one of the Kremlin palaces, until her husband’s violent assassination in 1905. However, not only did St. Elizabeth forgive the assassin, praying for his repentance and salvation; she visited him in prison, giving him a Gospel and icon to keep in his cell, and even asked the Tsar to grant him clemency.

But this was only the beginning of her transformation. Marie, her niece and foster daughter, recalls that

“from the death of her uncle, [...] her aunt [bore] in her eyes an ‘infinite sadness’ which was never to go away…. Marie and Dmitry felt Aunt Ella was planning something; something they could tell she was holding in her heart and they could see in her eyes….

Without telling anyone, it seems she decided to create her own monastery following the urban model of St. Basil the Great. She began simplifying her life greatly. Her bedroom was stripped of all its opulent and ancillary items, and pictures on the walls were replaced with icons. Her palace bedroom now appeared as a cell in a monastery…. Elizabeth returned all family jewelry she possessed while she was married to Serge. She then took what was left and bought an estate in Moscow in 1908. This became the Martha and Mary Convent of Mercy. Elizabeth was tonsured and became abbess of this monastery that focused on social outreach.” (Encountering Women of Faith, Vol. 1)

From princess to abbess, St. Elizabeth’s transformation was now complete. The monastery she founded still runs today true to her vision, operating a girl’s orphanage, medical center, family placement center for orphans, developmental center for children with cerebral palsy, and food bank. It has even inspired a daughter convent, the St. Elisabeth Convent in Minsk, Belarus, which has an even more robust social outreach, including an interesting and informative English-language website.

I have heard it said that it is likely St. Elizabeth would have been glorified as a saint even if she had not been martyred, but she did undergo martyrdom in 1918 at the beginning of the Russian Revolution. Thrown down a mine shaft together with several companions, and hit with hand grenades, the executioners reported hearing singing coming from the opening of the mine shaft. St. Elizabeth and those of her companions who survived the fall and explosion were singing the Cherubic Hymn and the Troparion of the Cross, comforting one another and tending to one another’s wounds.

Here is a beautiful, artistic depiction of St. Elizabeth’s life:

What Makes a Female Saint? “Manly Virtue,” aka Courage!

If holy eucatastrophe–responding to tragedy by offering our life to God, and receiving a perhaps unexpected resolution from Him, in the form of a transformed heart and life–is what makes a saint in general, is there anything unique to women saints in particular?

Timothy Patitsas, a contemporary American Orthodox philosopher, recently expounded an interesting Orthodox gender theology in his book, The Ethics of Beauty (see the chapter, “Only Priests Can Marry”). Patitsas builds his theology around the central idea of “chiasm” or cross-shape, according to which

men and women…are charged to inscribe the cross of Christ within their primary gender offices, within their respective gender callings…

The real way that Christian gender is inverted from the world’s is that in Christ each gender not only dies and is reborn, but in being reborn comes to a dynamic rest as the truest symbol not of its own life but of its partner’s role and life. Men come to symbolize best the feminine prophetic office, while women come to symbolize best the masculine kingly office… This is how the genders are deeply reconciled in Orthodox life, in a loving act of mutual indwelling and self-offering. (The Ethics of Beauty, emphasis original)

Among Patitsas’ observations are that in this gender chiasm, the male saints acquire what we normally think of as “feminine” virtues, such as gentleness and tenderness (perhaps why I feel so close to St. Nicholas and other male saints in my motherhood, such as SS. Paisios, Porphyrios, and Seraphim, as well as Elder Thaddeus, or even Christ Himself), while the female saints acquire what we think of as “masculine” virtues, like courage and fortitude. (In both Russian and Greek, for example, the word for courage is actually “manliness,” muzhestvo and andreia, respectively.) St. Elizabeth is certainly an example of courage, as well as other “masculine” virtues such as fortitude and vision.

I think we would be hard-pressed to find a female saint from any time in history who did not display incredible courage and fortitude at one time or another. For example, in the book of Esther, we read that Queen Esther prayed: “Give me courage, O King of the gods and Master of all dominion…. And save me from my fear!” (Esther 14:12, 19). Following her prayer, she approached the king to intercede for her people, “radiant with perfect beauty, and [looking] happy, as if beloved, but her heart was frozen with fear” (Esther 15:5). Esther was clearly terrified of this role, but because courage is “the ability to do something that frightens one” (Oxford Languages Dictionary), her steadfast resolve to act in the face of her fear, trusting in God, is all the more courageous.

Another example from the Old Testament is Solomonia, the mother of the seven Maccabean martyrs, who encouraged her sons to their martyrdom by “joining a man's heart to a woman's thought” (2 Maccabees 7:12). I love the imagery here: in the West, we often associate men with thought and women with heart (for example, in the Apollonian/Dionysian contrast), but here we see the exact opposite. A man’s heart signifies courage, while a woman’s thought signifies her care for her children, and both reside here in one holy person, who is a woman and mother.

In the New Testament and beyond, there are several female saints whom the Church calls “Equal to the Apostles” for their efforts to spread the Gospel to different cultures and places. One of these saints, Nina (or Nino) of Georgia, was the first to bring Christianity to the Georgian land. On what this must have been like for Nina, Anna Neill writes:

Like her, when you step out in obedience for a new task, you will be tempted to underestimate yourself, and others will discount you. We call that feeling “imposter syndrome”: I shouldn't be here, with these people who are better than me, trying to achieve an impossible goal. Your voice will quaver. You will want to hide. You may even flounder at the first try. In that moment, trust that the invitation to participate in divine love is the affirmation that you are enough…. God is working through you and with you. (Seven Holy Women)

So, to be a holy woman is to answer God’s call with courage, trusting in Him even when to do so is dangerous.

Hearing the stories of saints’ lives is an inspiring challenge: what would we do in their place? How can we train ourselves to get to the point where we would make the same courageous decisions as them? It starts with knowing their stories and asking for their intercession before God for us.

This concludes Part One, Receiving God’s Love. In Part Two starting with the next chapter, we will begin to consider this question: how can we return God’s love and love Him back?

Interview with Matushka Monica Olsen

Matushka

is a published writer who wants to share the ancient treasures she’s found with modern audiences by writing historical fantasy and fantastical history. (Most saints’ lives are fantastical without any additions on her part!) Her debut novel, In the Light of Abba Maximus, about the life of St. Maximus the Confessor, will be published in 2025. Her Storyletter goes out each month to readers who subscribe from her website, MonicaLOlsen.com. She continues to practice the craft of writing through membership and classes in The Habit writing community and Deacon 's Storyhearth community. A teacher for over twenty years, perhaps her favorite writerly adventure is teaching Creative Writing to teens through her local university’s Continuing Education program and at St. Athanasius Academy, an Orthodox online school. Finally, Matushka Monica collaborates with clergy and other mothers to create and teach curriculum for Sunday School, a Diocesan Parish Life Conference Program, and Vacation Church School.Thank you so much Matushka Monica for making time to speak with me today about our shared love for the saints!

Catie: I’m here with author and Matushka Monica Olsen! Matushka Monica, would you like to explain a bit about your work before we get into our conversation to give people a taste of what you write about?

Monica: Sure, Catie, thank you! I’m really happy to be here and talk to you. You can sign up for my storyletter on my website. I have three kids, and when we first became Orthodox about twenty years ago, I bought up all the children’s literature that existed about different saints, the illustrated books, the little chapter books, from St. Herman Press and Ancient Faith and a few others, but then I wanted more. There were no books about St. Maximus the Confessor whom my eldest son is named after–he’s 21 now. So I wrote a book! I wrote an illustrated book because he was about four or five at the time, and I sent it off to Ancient Faith. Jane Meyer, who was the Acquisitions Editor and also one of our favorite authors of children’s books, was so sweet and wrote me back, “I really love that you did this, but we don’t publish illustrations of torture! (laughs) So maybe you could think about writing it for middle schoolers, or as an action or adventure novel instead.” So I said, “sure, of course I can do that.” I didn’t know what I was doing, but I started writing it. Then, eight years later, I finally learned a little bit more about what I was doing, practiced, and got it ready to share with the world. So yeah, I wrote that one for my son, Maximus.

Catie: Awesome! I’ve been getting your emails through your email newsletter, which I recommend to anyone who’s listening to this. They’re really fun. I’m about to have my second baby, so I have a two-year-old and then a baby soon, and as someone who loves books, I think there’s a huge need in the Orthodox world for beautiful and literary saints’ lives, that our children can grow up with and love, that can be a gateway for them to love the saints. So that’s why I invited Matushka Monica to talk on this topic–I couldn’t think of anyone better to focus on this topic of saints.

Before I get into any specific questions about saints, I wanted to see if you had any thoughts overall on the project I’m working on, which is addressed to young Orthodox women who are striving to follow the Orthodox path, seeking union with God, which is so countercultural. It’s what we’re called to do, but it can seem unclear as to how to actually do that. So I’m trying to offer reflections from my life as to how we can grow in holiness. What I’m focusing on for the first part is receiving God’s love–learning how to accept His love–and for the final section of that part I’m focusing on the saints, getting to know them as people who channel His love to us. So I was wondering if anything comes to mind that you’d like to share on that.

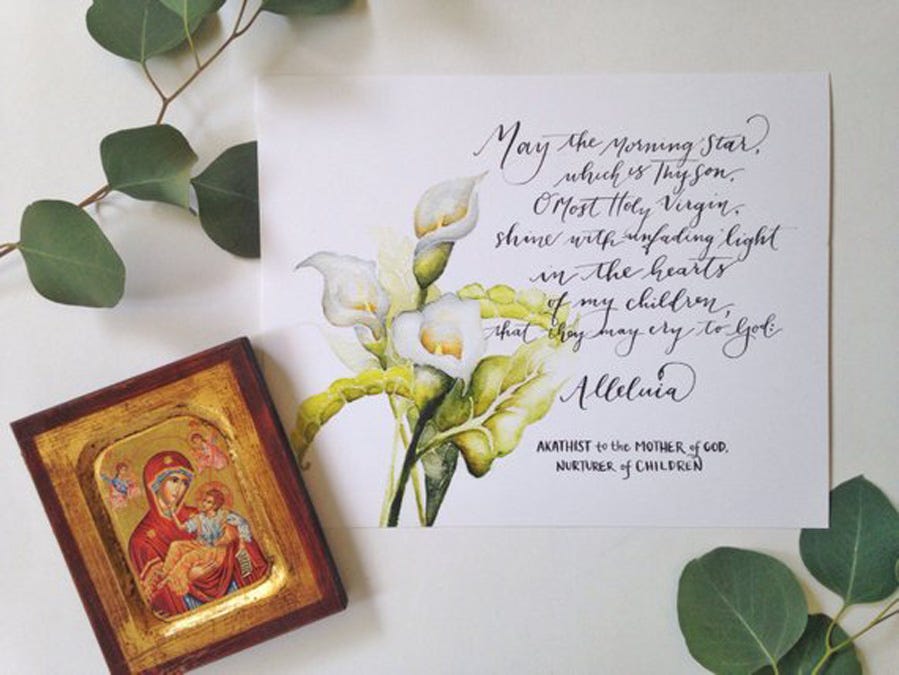

Monica: I love that you’re doing this for young women. I was thinking about that, and I think my biggest contribution to that conversation is to not be afraid to do things imperfectly, and maybe just a little bit at a time. I don’t know if it’s just because I’m a perfectionist, or because it’s a temptation for everyone, but when I was younger in my Orthodox faith, I thought I needed to do the idealistic version of things. What would happen is I would do it once or twice and then quit. For example, are you familiar with the Akathist to the Mother of God, Nurturer of Children?

Catie: Yes.

Monica: Okay. It’s one of my favorites, and you can buy it from St. Paisius Monastery. It’s basically thirteen stanzas of begging the Mother of God to help your children out in lots of different ways. When I first bought it for four or five dollars at our church bookstore, I was like, “I’m going to say this all the time for my kids!” But I did it a few times and then I quit.

Years later, my daughter’s godmother said, “You know, you could just do one ode per night.” If you do all thirteen odes, it takes about fifteen minutes. But if you only do one ode, it’s maybe a minute. So I was like, “okay, maybe I actually could do that.” So I started doing that, and over the course of two weeks I said the whole thing. It wasn’t my ideal, which was to do the whole thing every night of the year, 365 times. Doing it one ode per night meant that I only got it in 25 times per year, but you know what, for the previous few years I had done it zero times. Just a little bite at a time made a big difference.

It connects to what you’re talking about, with receiving God’s love, because doing it that way is more humbling and willing to say, “Well God, I’m here, and I’m not doing it great, but I’m showing up, so please help me.” I think you connect to God a lot more that way than when you approach Him like, “I’ve got it all together, and look what I’m doing for You.”

Catie: I love that. That actually also connects to the next part of the project, because I was going to say something along those lines, like “baby steps of holiness.” In my corner of Substack, there’s been a lot of conversation among the young moms about overcoming this perfectionism. I don’t know if all women have it, or all people have it, but it’s really relatable. It’s humbling to realize that something’s better than nothing, it doesn’t have to be the ideal. But God loves us, so if we’re going to receive that then, just like you said, we have to humble ourselves and receive the love instead of just performing.

So switching gears and talking more about the saints specifically, do you see it as God loving us through the saints, or the saints loving us, or both/and? How can we “use” the saints to grow closer to God, and how can we grow closer to the saints?

Monica: I’ll tell a story to answer that question, and I don’t mean this story to come across as, “therefore you should take my saint and do the same thing.” It could have been any saint, but God brought St. Paraskevi to me in a moment where I really needed a lot of comfort.

About five or six years ago, my husband and I were going through a struggle where we had just completely disagreed about a major life decision. We had been married for about twenty years at that point and never come across that 100% opposite, adamant, intense, anger about something. I dug in my heels and he dug in his, and our home went from being a normal, calm, happy home to the atmosphere or feeling of a war zone.

I was at a retreat, and the speaker was talking about wives and husbands and their interactions. He was saying about wives submitting to your husbands–it doesn’t mean every day, all day long, never mentioning what you want. Wives can talk to your husbands, you can share, communicate, work things out, and compromise. But sometimes, there might be something that you just cannot agree or compromise on, and your home will become a war zone. I thought, “ah! He’s describing me.” He said, in that case, the wife just needs to submit. I was a little bit angry, but more relieved, because I was tired of the war. He was like, look, maybe your husband’s wrong. But go ahead and submit, and trust the providence of God, that it will be okay.

So in the middle of that time, I also went to visit St. Paraskevi Monastery in southern Texas with a group of ladies from my parish. I loved it so much, I went back multiple times. I was talking with the Gerondissa [eldress, abbess] and pouring my heart out about my situation with my husband. She told me to pray the Canon to St. Paraskevi or the Supplication to the Mother of God every night. The Supplication is much longer, though, like 45 minutes to do, while the Canon is twelve minutes, maybe. She gave me a little service book that included the Canon. She said, “if you really don’t have time, just read the Odes of the Canon–just give it five, six minutes.”

I wasn’t particularly close to St. Paraskevi at that time, but I needed help, and she was there. A lot of times, reading through that Canon, I was just crying through it, sobbing the whole way through. Over the course of months and months, maybe years, I became close to St. Paraskevi, because she was helping me, holding me, comforting me, strengthening me, giving me courage to know that everything was going to be alright. Or even just giving me peace, whether it would be alright or not.

I wrote a novella during that time. The heroine refused to do something, so instead she had to go on this terribly difficult journey. She ended up doing the thing that she didn’t want to do anyway, and it was a blessing to her. I didn’t plan that out–it just happened to come out of my subconscious. But I think that’s what I was doing in my marriage, because after I submitted and we did the thing I didn’t want to do, it was a blessing to me.

I mention that novella–it was a fantasy novel–because there was a character who was like a guardian, and she was completely St. Paraskevi. Everything that she did to help the heroine was my heart of gratitude towards St. Paraskevi for helping me. I don’t think I realized at first that I was making St. Paraskevi a character in this novel, but eventually I did. So I went back to the Canon and typed out a list of every verb that it said she would do–like protect, shelter, even dance–and all of the nouns that it would call her–like bulwark, tower, guardian and so forth. Then I kept that page of words with me while I was writing so that I could refer to it.

I guess that was a long story, but the point of it was that just spending time with her every night is what made me come to know her and feel very close to her. When I leave church at the end of Divine Liturgy, there are a few saints that I find and kiss goodbye, and she’s one of them.

One of my friends, who was a catechumen at that time, asked me, “Why do you kiss those few saints?” They’re just really close to me. I want to touch base with them, tell them I love them and goodbye. It was a strange thing to hear as a catechumen, and I would have thought it was a strange thing for the first ten or fifteen years of being Orthodox, because I just hadn’t built that relationship yet. It’s the same way you build a relationship with any person–you spend time with them and over time you get to know them. That’s how it happened.

Catie: That’s amazing! It’s a whole new category when you think of these people, who in our timeline lived long ago, but in God’s timeline they’re just as alive as we are–maybe they’re more alive than we are since they’re in heaven with God. My uncle was telling me about his time on Mount Athos and what it meant for him. He said he realized that everything we teach is real. The saints aren’t just these magic amulets that we pray to in order to find something we lost. They’re real people whom we really get to know. That’s why you want to check in with them every Sunday after Liturgy.

I’m wondering, is this the St. Paraskeva who’s commemorated today, or is that a different one?

Monica: No, not the Serbian one whose nickname is Petka. She’s a different one, although I also have a relationship with her. This one is an early Christian virgin-martyr during the Roman Empire.

Catie: So interesting. I’m going to be sharing in my post about how I’ve been praying to St. Nicholas during potty training! Not that he was a parent or anything, but he is the patron of children, and he’s one of the closest saints to me, because I grew up going to a church dedicated to St. Nicholas. So there are these unexpected saints–even St. Xenia–people pray to her to find a spouse or a job or a home, but she didn’t have any of those things. So that’s really cool that St. Paraskevi, a virgin martyr, was able to help you in your marriage, through the guidance of the abbess of the monastery. We younger women who are recently or newly married can always use more guidance, so it’s nice to know we can turn to St. Paraskevi for that.

That was a really beautiful personal story. My final question was just if you had any more personal stories about getting to know the saints and how they brought you closer to God.

Monica: You mentioned St. Xenia. Recently, a dear sweet friend from Russia named Xenia was telling me I should pray to St. Xenia whatever my problem was, it didn’t matter, she would help me with it. She said, “I’m warning you, once you let her in, she will never leave. She’ll keep helping you for the rest of your life.” I was like, “well, I need that!”

So I found the Akathist to St. Xenia online and printed it off and asked my friend Xenia if she had any extra icons of St. Xenia lying around her house–she had just brought a bunch of extra icons to church to give away to people. I said, “I’d just really like to see her.” So she gave me a beautiful little icon. So I did the same thing–I did not one ode per night, but four odes! See how in these twenty years, I’ve progressed a little to four odes per night! (laughs)

What I’m trying to say is that it’s not some magical thing where you sit on your couch and think the right thoughts and try to have a conversation with a saint. It’s through the prayers that I’ve found the closest direct route to growing closer to the saints. Every time I read the words of the Akathist, I grow closer to St. Xenia. After doing that and having specific examples of ways she helped people, or specific things that the Akathist calls her, then in the middle of the day when I really need help, it just naturally comes to me: “St. Xenia, please help me, I can’t do this,” because I know that’s what she would do for me. But if I had never read the Akathist, I wouldn’t have thought to ask for her help in the middle of the day. So you could call a Canon or Akathist or icon a kind of portal you can go through, to get to a relationship with a saint or with God. The books, too, have helped do that for me. Reading books with the children about saints is how we got close to our first saints.

Catie: And writing about them even more so, I’m sure.

Monica: That’s the reason I write about saints. I just wish that everyone out there could meet my wonderful friends!

Catie: Thank you so much. It has been lovely getting to know you through this conversation. I’m so excited to follow your work and read your novel as soon as it comes out next year! Thanks again for talking with me today.

Monica: Thank you Catie! I appreciate it.

Thank you so much for reading and/or listening! We would love to hear from you in the comments what stood out to you from the post or interview. Here are some ideas to get you started…

Who is your patron saint? Who are your favorite saints, or ones you would like to get to know better?

Would you like to share any specific encounters you have had with a saint, or an instance when a saint interceded for you?

Do you have a favorite Akathist, Canon, or other prayer to a saint, or a favorite icon of a saint?

Also, here is a resource list of everything that Matushka Monica mentioned in her interview and some things I mentioned in my post plus some extra:

Monica L Olsen (Matushka Monica’s author website, where you can sign up for her storyletter!)

Akathists.com – A growing repository of Orthodox Christian Akathists. Prayers to Christ, The Theotokos, Saints, Angels, and to pray on specific occasions

Uncut Mountain Supply – My favorite icon supplier

Seven Holy Women by Melinda Johnson et al: reflections by seven authors on seven female saints, including information about their lives, and many journaling prompts and discussion questions.

Series on saints at Anna Neill’s blog: insightful reflections on several female saints and on the veneration of saints in general in the Orthodox Church.

Grand Duchess Elizabeth of Russia by Lubov Millar: this biography of St. Elizabeth has been on my to-read list forever. It just came back in print after a long time so I have yet to read it, but I have heard amazing things about it.

A Long Walk With Mary by Brandi Willis Schreiber: a deeply personal but beautifully universal memoir in which the author relates her own quest to know and love the Virgin Mary and to incorporate her as a vital participant in her spiritual life. (Check back next week for my interview with Brandi!!!)

A new series on Early Saints of the British Isles (A.D. 400-1000) by

!For children: Orthodox saints’ lives in picture book form, and saint dolls (“Snuggly Saints”)

The Ethics of Beauty by Timothy Patitsas: among many other insightful reflections, an Orthodox theology of gender.

- and which delves into the idea of Chiasm from TEoB!

Recording of Akathist to Matushka Olga of Alaska. St. Matushka Olga is the first (soon-to-be) glorified/canonized female saint of America. She was a native Alaskan woman, midwife, and healer who lived during the 20th century. Many invoke her intercession today for healing from various types of trauma and abuse, as well as support during pregnancy and birth.

Read previous posts in the series:

What’s Coming Next & Who It’s For

As he who called you is holy, be holy yourselves in all your conduct; since it is written, “You shall be holy, for I am holy.” (1 Peter 1:15-16; cf. Leviticus 11:44)

No Need to Get Married

All human souls are "feminine" in relation to God, the husband and the lover of each soul.

Read or Listen Next:

How and Why to Love the Mother of God: A Special Interview with

!!!How and Why to Love the Mother of God

This is a very special interview complementing “Chapter 4: Why ‘Manly Virtue’ is Womanly” from You Shall Be Holy: Reflections on Orthodox Womanhood.

Thank you for writing this post Catie! I once listened to a nun describing this movement of the genders towards completion in Christ. In our day and age people need this understanding more than ever.

An inspiring post, thank you! I’m about 13 years into my Orthodox journey (inquired a couple years before that), and there is so much depth that I haven’t come near to reaching. Getting to know the saints should be my desire, and I appreciate your concrete description of how to do so.