How A “Secular” Parenting Book Might Be More Deeply Orthodox Than A “Christian” One

Rethinking Spanking

For Juliana, who has shown me what love is

“I have been obedient with love to her words, / For she never once spanked me.”

—St. Paisius of Sihla, “The Life of Father Paisius”

If consequences are like the US military, spanking is like a nuclear weapon…It is important to be aware of the limited benefit, the real risks, and the damaging effects of corporal punishment.

—Dr. Philip Mamalakis, Parenting Toward the Kingdom: Orthodox Christian Principles of Child-Rearing

Have you ever questioned that spanking might not actually be an essential part of good parenting?

Like many of you reading this, I am a Christian mother who is devoted to the goal of raising children who will fulfill the great commandments: to love God and others. I have been told by some Christian parenting authorities that teaching and enforcing prompt, cheerful obedience is paramount in this endeavor. But is it really? And if we are to teach the Christian virtue of obedience, what is the best way to do so? Although the little years are probably always going to be challenging in some way, I have come to reject an emphasis on “immediate, cheerful obedience,” which I have come to believe may do much more harm than good. Instead, I am coming to embrace a more colorful, multi-dimensional approach, which actually turns out to be more traditional, and Orthodox, as well.

One fine day about two years into parenting, I pressed play on my audiobook of Hunt, Gather, Parent: What Ancient Cultures Can Teach Us About the Lost Art of Raising Happy, Helpful Little Humans by Michaeleen Doucleff, and was immediately engrossed. Hot on the heels of potty training, I was ready to try something new. Imagine my surprise to learn that “requiring” obedience, as if it were something that can be forced in human beings, is not a “thing” in the cultures which (unlike our American culture) raise the happiest and most helpful children.

Before I ever became a mother, I somehow came across the popular book, Raising Godly Tomatoes: Loving Parenting with Only Occasional Trips to the Woodshed by L. Elizabeth Krueger. The book has over one hundred five-star reviews on Amazon, and is popular on social media as well. In this book, the author advocates for teaching one’s children immediate, cheerful obedience, 100% of the time. This is to be enforced by spanking (“swats on the bottom”) and “outlasting.” Although outlasting is not defined in the book, here are a few sample quotations where it appears to give you a feel for the flavor of this parenting method:

“Quit being a pushover. Outlast him.”

“An occasional swat during this will speed things up, but the key is to outlast him until he gives in.”

“The first outlasting session can take an hour or longer as I described…in a previous chapter.”

Clearly, “outlasting” means that if our child does not obey us cheerfully right away, then we are being invited to enter a power struggle, which we must win! The author is completely convinced that this is the only way to parent as a Christian with “God-given authority” and that all other parenting approaches are “worldly.”

Truth be told, the simplicity of this approach (as well as its popularity among Christian mothers online) appealed to me, so I decided to give it a try. However, as my child grew, I saw clearly how detrimental this frequent spanking was to our relationship. It also didn’t work, since she thought it was a game. However, I had heard from some friends at church about the book Hunt, Gather, Parent and finally, the twelve-week hold on the Libby app came through. Soon after my daughter’s second birthday, I absolutely devoured the book and implemented as much of it as I could, right away.

I was surprised to see how, in comparison with the “universal [indigenous] style of parenting,” Doucleff lumps together all Western approaches, both secular and Christian. As she writes, Western parenting

focuses almost entirely on one aspect of the parent-child relationship. That's control--how much control the parent exerts over the child, and how much control the child tries to exert over the parent. The most common parenting “styles” all revolve around control. Helicopter parents exert maximal control. Free-range parents exert minimal. Our culture thinks either the adult is in control or the child is in control.

There's a major problem with this view of parenting: It sets us up for power struggles, with fights, screaming, and tears. Nobody likes to be controlled. Both children and parents rebel against it. So when we interact with our children in terms of control--whether it's a parent controlling the child or vice versa--we establish an adversarial relationship. Tensions build. Arguments break out. Power struggles are inevitable. For a little two- or three-year-old, who can't handle emotions, these tensions burst out in a physical eruption. (emphasis mine)

Coming from the high-control approach described in Raising Godly Tomatoes, this critique strongly resonated with me. What’s more, the more I read, the more the approach described in Hunt, Gather, Parent seemed to echo Orthodox anthropology and even soteriology. This was not surprising to me. As an Orthodox Christian, I have been taught to draw on the approach of St. Justin Martyr (2nd century) when considering non-Christian cultures. According to St. Justin, there is a “seed of reason (logos spermatikos)1 implanted in every race of men,” which functions as a preparation for them to receive the Good News.2 Examples include classical Greek philosophy, Chinese Taoism, and, perhaps, as we will see, the humble, peaceful, compassionate lifestyle of the Inuit peoples of North America.

Doucleff references the work of Joe Henrich, Steve Heine, and Ara Norenzayan, psychologists who discovered that “people from Western society, ‘including young children, are among the least representative populations one could find for generalizing about humans.’” To illustrate this principle, they came up with the clever acronym “WEIRD:” Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. We whom God has granted to belong to a “WEIRD” culture have much to learn from these non-Western, “primitive” cultures, as Doucleff shows us. After all, Orthodoxy is, like these other indigenous cultures, ancient and “non-Western.” To be specific, Orthodox spirituality is definitely Eastern, having been shaped especially by the Syriac Fathers such as St. Isaac of Nineveh and St. Ephraim. We will consider the Prayer of St. Ephraim below, while St. Isaac is remembered for his teaching that a “merciful heart” is “the heart’s burning for the sake of the entire creation, for men, for birds, for animals, for demons, and for every created thing.”3 Even demons, let alone human beings who bear God’s image, are to be the recipients of love. This compassionate approach is reflected in a more “therapeutic” approach to sin and salvation, rather than a more legalistic or juridical emphasis as we see in the Western Church. All this, as we shall see, is relevant to child rearing.

Far from teaching total depravity, Orthodoxy affirms that human beings are created good, and are still essentially good even though fallen. This positive view of humanity is echoed in Hunt, Gather, Parent, as the author voyages into three indigenous cultures to learn their methods of raising children. Michaeleen Doucleff visits Mayan families in the Yucatan, Inuits in Canada, and Hadzabe hunter-gatherers in Tanzania. What she finds there challenges many of the assumptions of Western parenting, which focuses as we noted above primarily on who has control in the parent-child relationship. In contrast, Doucleff encounters families who work together as a team from the youngest ages, whose children are cheerful, kind, and well-adjusted, taking responsibility and contributing meaningfully to their families and communities. Furthermore, they do all this without coercive tactics.

In the Yucatan, Doucleff meets a twelve-year-old girl who rolls out of bed and immediately starts washing dirty dishes on her spring break, without being asked, because, in her own words, she “likes to help her mother.” Parents in this culture raise extraordinarily responsible and helpful children, by welcoming, inviting, and assisting where appropriate (but not forcing!) the participation of children from the very youngest ages in work around the house. They treat children as full members of the family who are expected to contribute, rather than putting them in a separate “child” category where they have no real responsibilities. Furthermore, they do not really “praise” their children at all, but instead acknowledge their contributions to the work being done. All of this takes patience and a lot of time in the beginning. We can no longer rush through chores as efficiently as possible if we are involving our youngest children in the process. However, by working together on the same tasks voluntarily, work and fun become indistinguishable and chores become a joy.

This section has been extremely helpful in my household. I tried to change my parenting to be as similar as possible to that described in the book, and am very happy I did so. Six months later, my child thinks of herself as helpful (“I’m helpful!” she says after I thank her), enjoys fulfilling my requests (not always, but surprisingly often), and even helps strangers by picking up things that drop and handing them back. Sometimes she even thanks me for being helpful!

However, the next section really hit me between the eyes. When Doucleff travels north to Baffin Island to learn about traditional Inuit parenting, she finds that like the Mayans, Inuit parents teach above all by example–but where they truly shine is in their calm demeanor, raising peaceful, emotionally stable children. Inuit parents master their own anger, allowing them to experience children with love, patience, and kindness, even when they are misbehaving. Suddenly, I made a connection:

Even when your children and their playmates were noisy and made a mess in your house, you never scolded them or raised your voice in anger to them, but your silence showed them your love and understanding. Marveling in your divine patience and maternal compassion, we your children also cry: Alleluia!

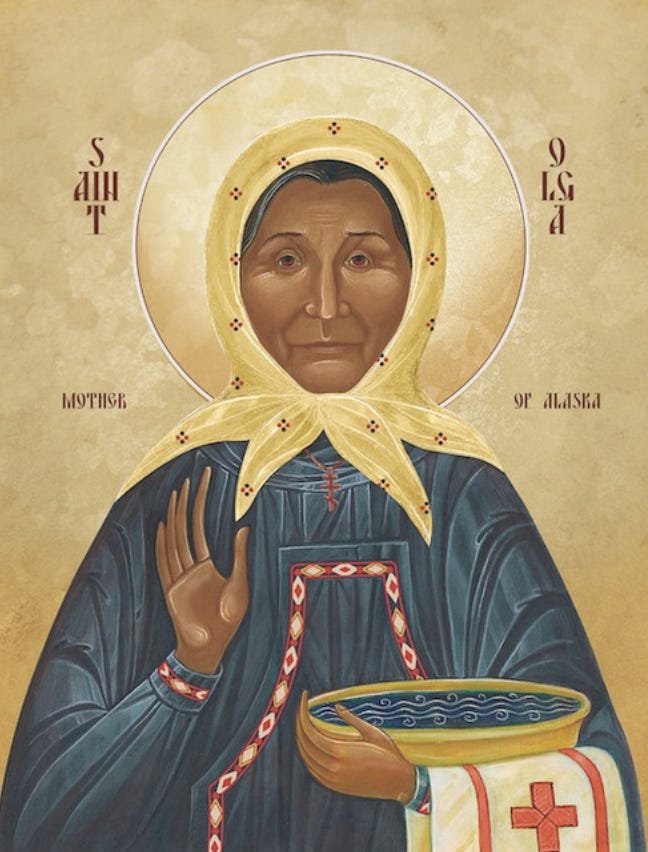

—Akathist to Matushka Olga of Alaska

Of course: the soon-to-be glorified St. Olga of Alaska belonged to this culture, albeit after it had been enlightened by Christianity. In fact there is a whole indigenous Alaskan Orthodox culture—not necessarily the one that Doucleff documents on Baffin Island, but overall belonging to the same demographic—“Inuit” is an umbrella term referring to the native peoples of Alaska, Greenland and Northern Canada. (To learn more about the Orthodox Alaskan culture, watch this documentary or read this book.)

Icon of Matushka Olga of Alaska

In any case, the kind of extreme peacefulness, self-control, and even taking responsibility for the mistakes of others, which Inuit parents model, are deeply Orthodox traits. Doucleff relates an anecdote in which her three-year-old daughter spills hot coffee in their hosts’ living room. The hosts have no reaction whatsoever other than to simply clean up the coffee, and when one admonishes the other, “You put your coffee in the wrong place.” As St. Seraphim said, “Acquire a spirit of peace, and thousands will be saved around you.” Consider also the prayer of St. Ephraim (4th century), prayed during Lent:

Lord and Master of my life, give me not the spirit of sloth, despair, lust of power, and idle talk.

Give rather the spirit of chastity [note: this could also be translated “self-control” and is more encompassing than the English “chastity”], humility, patience, and love to me, Thy servant.

Yea, Lord and King, grant that I may see my own transgressions and not judge my brother, for blessed art Thou unto the ages of ages. Amen.

I have seen firsthand as a parent how much my own sins cause my child to suffer. Instead, like the Inuit people model and the Orthodox tradition teaches, I should make sure I am repenting at least as much as I am expecting from my child. If she spills the coffee, I am to blame.

At the same time, I can see that obviously she is also to blame. So by blaming myself instead of her, I am practicing “unknowing” in order to be able to love her better. “Unknowing” is a skill in which women can excel as they grow in holiness, as Dr.

describes:[W]omen have this unavoidable responsibility… to be knowers, seers, givers of counsel… In Christ, however, women… now become mystical “unknowers”--that is, they unknow facts, things, and attributes, discovering how and when to look past them, to know instead persons. They thus become the special ministers to those in liminal states, such as children… In all these cases, they are better able than men to unknow the facts of diminished or unrealized human dignity and thus to affirm and nourish the personhood of vulnerable people. (The Ethics of Beauty)

It seems to me that this skill of “unknowing” is deeply established not only in the Inuit tradition of parenting, but in Orthodox cultures as well. Consider this anecdote from the childhood of St. Paisius the Athonite:

My mother…noted my mischief, but she had a certain noble spirit about her. When I did something naughty, she would turn her face away and pretend not to see me, so as not to make me sad by having to scold or reprimand me. But this behavior of hers would break my heart. It made me think, “Look, I did this mischief and my mother not only does not punish me, she also pretends not to even see me! I’ll never do this again! How can I upset her like that?” With her stance, my mother was able to help me even more than if she had slapped me. (Family Life)

Other tools in the Inuit toolbox also seem to echo the idea of “unknowing.” For example, one of the techniques is simply to ignore a child engaging in inappropriate behavior. The parent stares off into the distance, a couple inches above their head, pretending they are not there. In this way, the misbehavior receives no attention at all, and naturally, over time it withers away.

However, “unknowing” and calmness are not meant to condone nor encourage bad behavior through permissiveness. Inuit parents also actively devalue misbehavior by associating it with childishness and immaturity, as well as by using many other tools which are explored in the book. They physically prevent children from hurting one another by picking them up and holding them close. They also issue clear guidance, in the form of information: “if you climb up there, you’ll fall and get hurt” (not: “don’t climb up there”). They set and enforce limits with compassion and patience–and because they maintain a calm and peaceful demeanor and atmosphere throughout, they proactively teach this peacefulness by example.

This mind shift has been my single biggest takeaway from the book. I do not need to judge my own or anyone else’s child and lose my peace. Instead, I need to ask God to “give rather a spirit of self-control, humility, patience, and love to me, Thy servant,” and teach these to my child through my example. These words of St. Porphyrios of Kafsokalyvia could surely have been spoken by Matushka Olga as well:

What saves and makes for good children is the life of the parents in the home. The parents need to devote themselves to the love of God. They need to become saints in their relations to their children through their mildness, patience, and love. They need to make a new start every day, with a fresh outlook, renewed enthusiasm and love for their children. And the joy that will come to them, the holiness that will visit them, will shower grace on their children. (emphasis mine)

The rest of the book was full of other interesting and effective insights into parenting. For example, the final section of the book, where Doucleff visits Hadzabe families in Tanzania, encouraged me to try to find more “alloparents” for my child. Alloparents are older children or adults other than a child’s own parents, who spend time with a child. As Doucleff notes, for the majority of human history prior to our WEIRD culture, children have spent the bulk of their waking hours playing with and learning from other children, as well as adults other than their own parents (such as extended family). This is beneficial for children, who enjoy the socialization, as well as for parents, who get to rest or turn their attention to tasks other than child-rearing. A church congregation is a great place to meet potential alloparents, and after reading this book, I decided to hire a teenage girl from our parish to watch my older daughter a few times a month. It has been a great decision, as my child grows in relationship with an older role model from church, while my husband and I get to rest a bit.

Was there anything lacking in Hunt, Gather, Parent? While reading Doucleff’s oft-repeated claim that indigenous parents “never force their children to do anything,” I was slightly reminded of the famous study that “proved” that consumption of animal products is detrimental to one’s health, based on a study conducted in Crete during Great Lent. The researchers wrongly concluded that because the healthiest people in the world ate no animal products during the entire time they were being observed, that they never ate any animal products at all, and that this must be the secret to their longevity. In reality, of course, Greek food can be very rich and full of animal products, especially lamb! As outsiders looking into a culture, surely there is more to the story that we will never understand, no matter how excellent the book is.

In any case, obedience certainly is a Christian virtue. But besides finding the right way to teach it, we must first rightly understand it ourselves. This is where the Raising Godly Tomatoes model falls short and where we can learn from an Orthodox approach. In Raising Godly Tomatoes, the author bases her concept of what obedience is and how to teach it on her own reading of the Bible, specifically her observation of how God commands others and is obeyed. The parent puts herself in the place of God. In contrast, Orthodoxy practices obedience as a form of asceticism. All of us are to be under some form of obedience, “toward our spouse, our own parents, those in authority, and God” (Parenting Toward the Kingdom). The struggle to be obedient in these ways brings us face to face with our own sinfulness so that we can then repent of it. In this sense at least, parents and children find themselves on a more level playing field: we all have sin and we all need to repent.

(This does not mean that the family devolves into a democracy, but that the parents lead with Christlike love rather than coercion. Nor is this because Orthodoxy or Inuit culture have been infiltrated by “worldly philosophies” and “psychology,” as Krueger might claim. As for psychology and neuroscience, many Orthodox elders and eldresses in our own times, such as Mother Siluana Vlad and Elder Symeon Kragiopoulos, have taught and lived out the truths proper to these fields, seeing them as reinforcing what we know from centuries of ascetic wisdom.)

And so in Orthodoxy as among the Inuit people, parents are neither scandalized nor overly upset by children’s misbehavior. For example, children are to be present for church services along with their parents. There is no “child’s service.” At the same time, very rarely do Orthodox churches have a “cry room” (although streaming the service online or in another room, or broadcasting over speakers outside, are most welcome to parents and caregivers for those moments when children just can’t be inside). In the sanctuary during services, children are allowed to squirm about within reason and perhaps make a bit of noise, while they are still learning the proper behavior. Perhaps this is because we affirm, through experiential wisdom and tradition, that human nature is good, even though fallen. We are not totally depraved as the reformers would have it, drawing on the darkness of their own limited human reason. As such, children are worthy of being treated with patience, understanding, compassion and every other virtue. After all, they are the ones whom we must turn and become like if we want to enter the Kingdom of Heaven.

True obedience (as opposed to external conformity), like the other virtues, is a sign of maturity. It “comes from the inside, voluntarily, proceeding from a person who acts with agency.” It is “not imposed from the outside” and “not a cringing response to power wielded.” For this reason, “we cannot force compliance or demand obedience; we can only practice and help our children to practice those habits that we know they need” (Patterns for Life). Just as Doucleff documents in her excellent book, behavior is caught, not taught. If we want obedient children, we must model obedience and use our parental authority “to establish a culture and atmosphere in the home that allows our child to acquire all the values and virtues of the Kingdom of God, including obedience” (Parenting Toward the Kingdom). This is because our “parental authority…is about being in control of the routines, rituals, rules, and regulations of the home more than in control of our children. One is an act of love and the other an act of oppression” (Parenting Toward the Kingdom).

A better way to foster the kind of atmosphere in which healthy and true obedience can take root, as Dr. Mamalakis shows, is by establishing a culture of listening in the home. For “obedience,” whether in English or any other language, comes from a root word, “to hear” or “to listen”: ob-audire in Latin, по-слушать in Russian, and as Dr. Mamalakis notes, in Greek as well. When we listen to our children, they listen to us. (For a plethora of helpful suggestions and insights on fostering this culture of listening in the home, please see the incredible book Parenting Toward the Kingdom.)

If there is one thing I have learned through this reflection, it is to be more discerning about which “Christian” resources I employ. Raising Godly Tomatoes says that “if you allow your two year old to be selfish, you are just allowing him to sin.” But Orthodoxy teaches that this way “of describing and interacting with childhood [is] too narrow” (Patterns for Life), because “our children are good, all the time, and they make good and bad decisions, all the time” (Parenting Toward the Kingdom). And so trying to overcome sin by simply teaching and enforcing rote obedience is far from enough. Instead, at St. Paisius the Athonite tells us, “When your children are still small, you have to help them understand what is good. That is the deepest meaning of life.”

Stay tuned for Part 2: The Whole-Brain Child Meets Orthodoxy

Thank you for reading! What are your favorite parenting books, resources, or perspectives? Which ones are you currently reading and pondering? Do you love Raising Godly Tomatoes and I got it all wrong? I’d love to hear from you, so please comment and share!

My Other Favorite Parenting Books Besides Hunt, Gather, Parent:

Simplicity Parenting: Using the Extraordinary Power of Less to Raise Calmer, Happier, and More Secure Kids by Kim John Payne: a Waldorf teacher shows us how to simplify and slow down our family lifer

Abbie Halberstadt books, specifically M Is for Mama: A Rebellion Against Mediocre Motherhood and Hard Is Not the Same Thing as Bad: The Perspective Shift That Could Completely Change the Way You Mother a seasoned mother of ten encourages and challenges us with God’s word to love and appreciate our children while setting reasonable boundaries and limits for them

Patterns for Life: An Orthodox Reflection on Charlotte Mason Education by

and : two home-educating mothers interpret Charlotte Mason through an Orthodox lens, offering insights on human nature and how we can raise holy childrenParenting Toward the Kingdom: Orthodox Christian Principles of Child Rearing by Dr. Philip Mamalakis: a licensed therapist, professor, and father of seven offers an Orthodox approach to “parenting with the end in mind”

Sally Clarkson books, specifically Seasons of a Mother’s Heart: Heart-to-Heart Encouragement for Homeschooling Moms and Giving Your Words: The Lifegiving Power of a Verbal Home for Family Faith Formation: an evangelical, incarnational approach to being missionaries of God’s love to our children

Children in the Church Today: An Orthodox Perspective by Sr. Magdalen: reflections on prayerfully and compassionately raising children in the Orthodox Church

Currently on my shelf, in-progress:

The Continuum Concept: In Search of Happiness Lost by Jean Liedloff

The Whole-Brain Child: 12 Revolutionary Strategies to Nurture Your Child's Developing Mind by Daniel Siegel and Tina Bryson (“especially recommended reading” by Dr. Philip Mamalakis of Parenting Toward the Kingdom)

The Happy Dinner Table: The Path to Healthy and Harmonious Family Meals by Anna Migeon

Free-Range Kids: How to Raise Safe, Self-Reliant Children (Without Going Nuts With Worry) by Lenore Skenazy (“especially recommended reading” by Dr. Philip Mamalakis of Parenting Toward the Kingdom)

On my to-read list:

Good Inside: A Guide to Becoming the Parent You Want to Be by Dr. Becky Kennedy

No-Drama Discipline: The Whole-Brain Way to Calm the Chaos and Nurture Your Child's Developing Mind by Daniel Siegel and Tina Bryson

Parenting from the Inside Out: How a Deeper Self-Understanding Can Help You Raise Children Who Thrive by Daniel Siegel (“especially recommended reading” by Dr. Philip Mamalakis of Parenting Toward the Kingdom)

Our Church and Our Children by Sophie Koulomzin

Don’t have time to read Hunt, Gather, Parent? Listen to this one-hour interview with the author on the 1000 Hours Outside podcast with Ginny Yurich.

Logos has no exact English equivalent and can be translated as ‘principle’ or ‘reason,’ that which gives something ‘its unique character…what causes it to be, its principle and final end.’ Jean-Claude Larchet, The Spiritual Roots of the Ecological Crisis

St. Justin Martyr, Second Apology, Chapter Eight

The ascetical homilies of St Isaac the Syrian, Brookline, MA: The Holy Transfiguration Monastery 1984, pp. 344-345.

Looking back, the thing about how I parented that I most wish I could change was spanking. I didn't do it a lot, but I believe it's possible not to "need" to, and believed it then - there just weren't very helpful resources 40 years ago. It's the parent's attitude that needs to change, of course. Aside from the "total depravity" perspective of Evangelicals, the basis for that kind of parenting seems to be about Management in the Machine-era sense, the influence of the Modernity in which we all swim on whatever people label as "Biblical, in spite of the best intentions of loving parents.

Though I was in an Evangelical environment when my children were very young, I think what saved me from the excesses of the so-called "Biblical" child-raising schemes, including demanding instant obedience, were the good things my own parents did in raising me (though I was spanked, and knew even as a child that all that did was instill in me fear of spanking). Both of my parents were Catholic, but there was also a very strong Italian cultural factor on my mom's side, which I believe mitigated her own feelings of inadequacy about parenting. I grew up when free-ranging was the norm, which was also helpful, and "alloparents" were plentiful, with this light duty expected in the community, esp the church community.

It sounds like this book needs to be the companion volume to Dr Mamelakis'.

Dana

Catie, you always seem to publish exactly the piece I need for the moment I'm currently in. We've been struggling with our three year old, she is a very spirited and sensitive soul who gets easily dysregulated and struggles to manage her emotions. I purchased Parenting Towards The Kingdom a couple of weeks ago and am finding it so helpful, its given me so much to reflect on and made me realise how much I need to learn as a parent! I love how Dr Mamalakis grounds his advice in the important truth that our children are also icons of God and thus worthy of love, respect and veneration. Such a different perspective from the strict Calvinist "total depravity" I was raised with! Have just ordered Hunt Gather Parent, it's been recommended to me so many times and I really trust your recommendations, you've never recommended a bad book :) Have made notes of all the other books you listed so I can work through them gradually.